Gaining public trust: monitoring shale gas

Prof. Michael H. Stephenson

Prof. Michael H. StephensonMike Stephenson, British Geological Survey

January 2014

Monitoring and regulation are vital for orderly and sustainable energy development - and public and investor confidence. In the case of shale gas, public confidence is particularly important. At the moment, public confidence in shale gas in Europe is rather low with the result that most activity prompts protests. These are dismissed as ‘nimbyism’ by companies and supporters of shale gas, but they are still enough to slow development down and maybe enough to stop it entirely.

Two months ago I visited oil sands and shale gas operations in Alberta, Canada. Alberta is sitting on enormous resources but there is a big challenge in selling their sustainability to Canadians because both oil sands and shale gas extraction have impacts on atmosphere, wildlife and water. The new ‘Alberta Environmental Monitoring Agency’ will monitor environmental effects in detail providing real time data that is scientifically credible, accessible, open and independent from companies. It’s hoped that this flow of data will reassure the public that resource management is within sustainability limits and will immediately show if something has gone wrong.

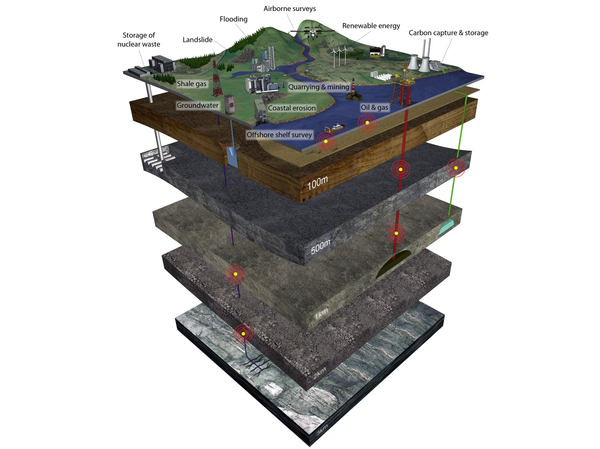

In Europe there are serious questions about whether we should be taking up another fossil fuel like shale gas in a big way but many experts think that shale gas could have a role in the next few years as a bridge to low carbon, especially if it displaces coal-fired electricity. But to allow it to go ahead, Britain and Europe should consider a more comprehensive monitoring system so that subsurface usage can be managed to the satisfaction of the public. The monitoring system should go beyond the immediate site of the drilling, looking at the wider geological basin, particularly in the case of dense activity in the subsurface. The monitoring should include subsurface sensors - not just microseismics but also sensors for groundwater and rock properties. It should also go above ground to look at fugitive emissions and surface behaviour through INSAR for example. Such a large scale monitoring system might go a long way to reassuring the public that we can manage the subsurface sustainably and safely. Monitoring of this type will also be pertinent to other energy activities that depend on geological containment or understanding of deep flows, for example carbon capture and storage (CCS), underground gas storage, geothermal and radioactive waste disposal.

In the UK and Europe we already have bits of the network in place. In the UK, for example, the BGS national seismic monitoring network and the BGS methane groundwater survey are measuring the all-important natural baselines that will help us to establish whether changes have happened following drilling. Many geological surveys in Europe also carry out these roles but we should increase the density of monitoring, and expand to include other aspects of concern to the public – for example fugitive emissions and ground subsidence - and learn to present this data more freely, openly and transparently.

At the British Geological Survey we are planning a project called the ‘Energy Test Bed’ which will be a new national monitoring network distributed in five key regions of Britain with the aim of creating regional-sized subsurface natural laboratories. Each region would be chosen for its particular energy challenge and subsurface geology type. For example the northwest of England could be chosen to monitor possible shale gas drilling including high density seismic monitoring, electrical resistance tomography monitoring of shallow aquifers, satellite surveying and downhole geodynamic monitoring. Other areas with different challenges may warrant a different suite of sensors; however the full 5 natural laboratories would cover a representative range of geological and energy-related conditions for UK development.

A monitoring network of this kind would greatly improve our knowledge of Britain’s subsurface and contribute to increased efficiency and environmental sustainability. We’ll have to make the data completely open and transparent, display it and encourage the public to understand what it means.

A real-time national monitoring system, the science results of which are communicated transparently and effectively, might go a long way to reassuring the public that shale gas drilling and other subsurface activities can be done safely and sustainably.